Hedge funds fees are often described as one of the most complex and controversial cost structures in the investment world. From management fees and performance fees to high-water marks and fund expenses, investors frequently struggle to understand how hedge fund fees actually work and how much they reduce net returns. Unlike traditional investment vehicles, hedge funds rely on a unique fee structure designed to reward active management, alpha generation, and risk-adjusted performance. Explore the detailed article at Tipstrade.org to be more confident when making important trading decisions.

What Are Hedge Funds Fees?

Hedge funds fees refer to the total costs charged by hedge fund managers to operate, manage, and generate returns for investors. These fees are typically deducted directly from fund assets, meaning investors see net returns after all costs have been applied.

Unlike ETFs or mutual funds, hedge funds do not rely on a single expense ratio. Instead, they use a multi-layered fee structure that compensates managers for both ongoing operations and investment performance.

In practice, hedge fund fees reflect the complexity of strategies employed, such as long/short equity, global macro, or event-driven investing. Industry data from the CFA Institute shows that hedge funds often justify higher fees by claiming superior risk management, access to specialized markets, and advanced research capabilities.

However, understanding how each fee works is critical, because even small percentage differences can significantly erode long-term returns through compounding effects.

See more

- Hedge Funds Report: A Comprehensive Analysis of Performance, Strategies, and Industry Trends

- Index Funds vs Mutual Funds: Understanding the Key Differences Before You Invest

- Top Index Funds to Consider for Long-Term Investing

- Risks in Index Funds: What Every Investor Should Understand

How Hedge Fund Fees Differ from Mutual Funds and ETFs

One of the most common questions investors ask is why hedge fund fees are significantly higher than those of mutual funds or ETFs.

The answer lies in both structure and incentives. Mutual funds typically charge a flat annual expense ratio, often below 1%, while ETFs may charge less than 0.20%. Hedge funds, by contrast, charge performance-based fees in addition to fixed management fees.

From an industry perspective, hedge fund managers argue that performance fees align their interests with investors.

According to research published by Investopedia and Morningstar, performance-based compensation theoretically motivates managers to pursue alpha rather than simply track a benchmark.

Critics, however, point out that high fees can still exist even when long-term performance fails to exceed passive alternatives.

The “2 and 20” Fee Structure Explained

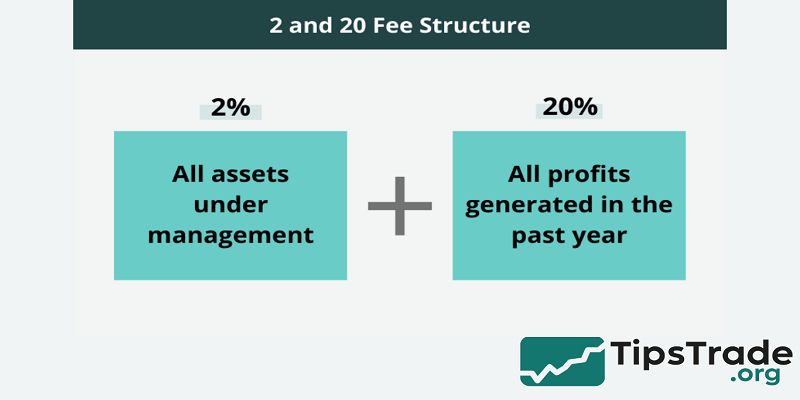

The most widely recognized hedge fund fee model is known as “2 and 20.” This structure includes a 2% annual management fee and a 20% performance fee on profits. While variations exist, this model has dominated the hedge fund industry for decades.

Historically, the 2 and 20 structure emerged in the 1960s and became popular as hedge funds positioned themselves as exclusive, skill-based investment vehicles.

Academic research from Harvard Business School suggests that while this structure can incentivize active management, it may also create asymmetric risk-taking behavior if not properly controlled by investor protections such as high-water marks.

Management Fees in Hedge Funds

The management fee is charged regardless of whether the hedge fund generates profits. Typically calculated as a percentage of assets under management (AUM), it covers operational costs such as research staff, trading infrastructure, compliance, and administration.

In real-world hedge fund disclosures, management fees usually range from 1% to 2%, though large institutional investors often negotiate lower rates.

From an investor’s perspective, management fees represent the “cost of access” to the fund’s strategy.

While critics argue that these fees reduce returns during periods of underperformance, supporters claim they ensure organizational stability and professional oversight.

Performance Fees and Incentive Fees

Performance fees, also called incentive fees, are charged only when the hedge fund generates profits.

Typically set at around 20%, these fees are calculated after management fees have been deducted. The rationale is straightforward: managers earn more only when investors earn more.

However, empirical studies from the SEC and academic journals show that performance fees can significantly reduce net returns over time. In some cases, investors may pay substantial incentive fees during strong years, only to experience losses later without fee refunds.

This asymmetry makes understanding additional safeguards, such as high-water marks, essential.

Additional Hedge Fund Fees Investors Often Overlook

Beyond management and performance fees, hedge funds may charge additional expenses that are less visible but equally impactful. These costs are typically disclosed in offering memoranda rather than marketing materials.

Common additional fees include:

- Administrative and legal expenses

- Custody and audit fees

- Trading and transaction costs

- Financing and borrowing costs

While each fee may appear small individually, combined expenses can add another 1–2% annually. Research from the Financial Analysts Journal emphasizes that total cost analysis, not headline fees, provides the most accurate picture of hedge fund affordability.

High-Water Marks and Investor Protection

A high-water mark ensures that a hedge fund manager only earns performance fees on new profits. If a fund experiences losses, it must recover those losses before charging incentive fees again.

From an investor protection standpoint, high-water marks are essential. They prevent managers from earning repeated performance fees on the same gains.

Industry best practices, as recommended by the CFA Institute, consider high-water marks a minimum standard rather than a premium feature.

A Real-World Example of Hedge Fund Fees

To illustrate how hedge fund fees work in practice, consider a hypothetical investor allocating $1,000,000 to a hedge fund using a 2 and 20 fee structure.

| Item | Amount |

| Gross return (12%) | $120,000 |

| Management fee (2%) | -$20,000 |

| Net profit before incentive fee | $100,000 |

| Performance fee (20%) | -$20,000 |

| Net investor return | $80,000 |

In this example, the investor earns an 8% net return instead of the 12% gross return. While still profitable, fees consume one-third of total gains. Over a 10–20 year horizon, this difference compounds significantly.

How Hedge Fund Fees Affect Long-Term Returns

The long-term impact of hedge fund fees is often underestimated. Even small fee differences can translate into millions of dollars lost over decades.

Research from Vanguard and Morningstar consistently shows that fees are one of the strongest predictors of net investment outcomes.

In comparative studies, many hedge funds underperform low-cost index funds after fees. However, select managers with persistent alpha may justify higher costs. The challenge for investors lies in identifying those managers in advance, which academic literature suggests is extremely difficult.

Can Investors Negotiate Hedge Fund Fees?

Institutional investors such as pension funds and endowments frequently negotiate hedge fund fees.

Common concessions include reduced management fees, performance fee hurdles, and customized fee breakpoints.

Side letters, which modify standard fee terms, are a common tool in these negotiations. While retail investors rarely have this leverage, understanding that fees are not always fixed empowers investors to ask better questions and evaluate alternatives.

Are Hedge Fund Fees Worth It?

Whether hedge fund fees are worth paying depends on several factors, including performance consistency, risk management quality, and portfolio diversification benefits.

For some investors, hedge funds provide exposure to strategies unavailable through traditional products.

However, regulatory bodies such as the SEC emphasize the importance of fee transparency and investor education.

Paying high fees without clear performance justification increases the likelihood of long-term underperformance.

Conclusion

Hedge funds fees are complex, layered, and often misunderstood. While they can align manager incentives with investor outcomes, they also pose a significant drag on long-term returns. Understanding how management fees, performance fees, and additional expenses work empowers investors to make informed decisions. Ultimately, hedge funds are not inherently good or bad investments—but their fee structures demand careful scrutiny. For investors willing to do the analysis, transparency and education remain the most effective tools for protecting capital and maximizing net performance.