Value investing is an investment strategy that focuses on buying stocks that are undervalued compared to their true worth. This approach aims to find companies with strong fundamentals that the market has overlooked, allowing investors to buy shares at a lower price and benefit when the market corrects. Value investing requires careful analysis and patience to achieve long-term growth.

What Is Value Investing and Why It Matters

- At its core, value investing is an investment philosophy based on identifying undervalued securities — stocks that trade for less than what they are truly worth.

- The assumption is that markets often overreact to short-term news, creating opportunities for patient investors to buy quality companies at a discount.

- Benjamin Graham, author of The Intelligent Investor (1949), first formalized this method.

- He argued that the market is not always efficient — prices can deviate from intrinsic value due to investor psychology, panic selling, or temporary misjudgments.

- His famous metaphor describes the market as “Mr. Market”, an emotional partner offering to buy or sell stocks at fluctuating prices.

- The wise investor waits until Mr. Market offers a good deal.

- Warren Buffett, Graham’s most famous student, evolved the philosophy further.

- Instead of focusing solely on cheap stocks, Buffett looked for great companies at fair prices — businesses with strong brands, predictable cash flows, and durable competitive advantages (known as economic moats).

- Today, value investing remains a cornerstone of professional portfolio management, practiced by asset managers like Dodge & Cox, Oakmark, and Vanguard Value Index Funds.

- Despite periods of underperformance compared to growth stocks, studies from Morningstar (2024) show that value strategies tend to outperform growth over long horizons, especially after inflationary or high-rate cycles.

The Core Philosophy Behind Value Investing

Value investing is built on several key principles that blend rational analysis with emotional discipline.

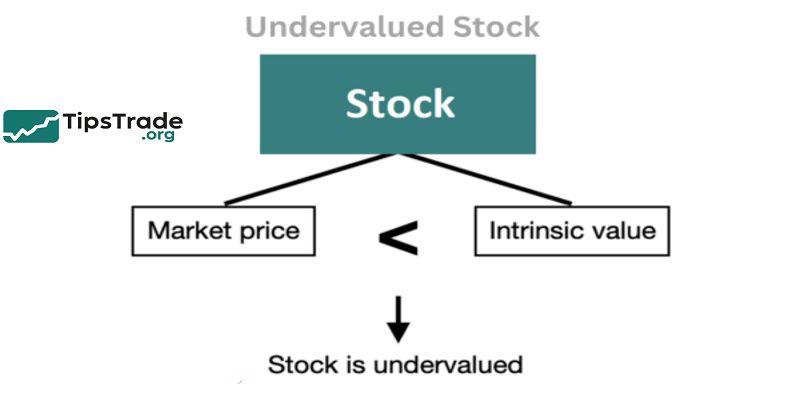

The Concept of Intrinsic Value

Intrinsic value represents what a business is truly worth based on fundamentals such as:

- Earnings and cash flows

- Assets and liabilities

- Growth potential

- Competitive advantages

The goal is to estimate this intrinsic value and compare it to the market price. When a company trades below its intrinsic value, it’s considered undervalued.

The Margin of Safety

- Coined by Benjamin Graham, the margin of safety means buying a stock only when it’s significantly cheaper than its calculated value — typically 20–30% below.

- This buffer protects investors from errors in judgment, unexpected news, or market volatility.

The Long-Term Perspective

- Value investing requires patience. Markets may take years to correct mispricing, but when they do, the rewards can be substantial.

- Buffett often holds stocks for decades, allowing compounding returns to do the heavy lifting.

Quality Over Quantity

- Modern value investors prioritize quality businesses — companies with strong management, consistent profits, and sustainable moats — even if they’re not the cheapest.

- As Buffett put it, “It’s far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price.”

How to Spot Undervalued Stocks

Value investors use financial metrics to assess whether a stock is trading below its intrinsic value. The key is to interpret numbers wisely, not mechanically.

| Metric | Meaning | How Value Investors Use It |

| P/E Ratio (Price to Earnings) | Stock price ÷ earnings per share | Low P/E may signal undervaluation — but check if earnings are stable. |

| P/B Ratio (Price to Book) | Market price ÷ book value | A P/B under 1 can suggest the stock trades below asset value. |

| PEG Ratio | P/E ÷ growth rate | PEG < 1 indicates value relative to growth. |

| Dividend Yield | Dividend ÷ price | High yield = steady cash flow, but avoid unsustainable payouts. |

| Free Cash Flow (FCF) | Operating cash flow – capital expenses | Positive FCF = financial flexibility and resilience. |

(Sources: CFA Institute, Investopedia, Morningstar 2024)

A single ratio never tells the whole story — a low P/E might mean declining sales, or a low P/B could hide poor assets. The key is context: compare ratios to industry peers and historical averages.

The Human Side of Value Investing

Numbers alone can’t capture a company’s true worth. The best value investors look beyond financial statements to evaluate intangible strengths.

Management Quality

- A great business can be ruined by poor management. Look for executives with integrity, clear capital-allocation discipline, and shareholder-friendly behavior.

- Reading annual reports, earnings calls, and shareholder letters can reveal whether leadership is focused on long-term value or short-term stock prices.

Competitive Advantage (Economic Moat)

Companies that can defend their profits through strong brands, patents, cost advantages, or network effects are worth paying for. Examples include:

- Coca-Cola: global brand loyalty

- Apple: ecosystem lock-in

- Visa: network effects and high switching costs

Industry Structure

- Some sectors (e.g., energy, banking, consumer staples) lend themselves better to value investing due to tangible assets and stable earnings.

- By contrast, fast-moving tech firms may be harder to value accurately.

Valuation Techniques for Estimating Intrinsic Value

Different investors use different valuation methods depending on industry type and data availability.

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF)

- DCF projects future free cash flows and discounts them back to present value using a discount rate (often WACC).

- This method is theoretically robust but highly sensitive to assumptions — small changes in growth or discount rate can swing valuations by 20–30%.

Relative Valuation

- Compares a company’s multiples (P/E, EV/EBITDA, P/B) with industry peers.

- Useful for benchmarking — if similar companies trade at higher multiples, your target may be undervalued.

Asset-Based Valuation

- Appropriate for firms with significant tangible assets, like real estate or manufacturing.

- You sum up the fair market value of assets minus liabilities to estimate net asset value (NAV).

Earnings Power Value (EPV)

- Popularized by Columbia University’s Bruce Greenwald, EPV values a firm based on normalized earnings adjusted for reinvestment needs — a practical alternative when growth projections are uncertain.

- In practice, professional investors often triangulate using multiple methods to cross-validate intrinsic value.

When Value Investing Outperforms

Value investing doesn’t win every year, but it often shines under certain market conditions:

| Market Condition | Why Value Performs Better |

| Rising interest rates | Growth stock valuations compress; investors favor earnings today. |

| Inflation periods | Tangible-asset companies (energy, materials) gain pricing power. |

| Post-crisis recovery | Mispriced stocks rebound faster as fundamentals normalize. |

| Bear markets | Defensive, cash-rich firms outperform speculative growth names. |

According to a Brown Advisory Report (2024), during the 2022–2024 global inflation cycle, the MSCI World Value Index outperformed the MSCI Growth Index by +11.8% annually.

That said, patience is vital. Between 2010–2020, growth investing dominated, fueled by ultra-low interest rates and tech innovation. Yet when conditions changed, value made a strong comeback — a reminder that market cycles always revert.

Avoiding Common Value-Investing Mistakes

Even experienced investors fall into traps when chasing cheap valuations.

The “Value Trap”

- A value trap is a stock that appears cheap but keeps getting cheaper because its fundamentals deteriorate.

- Examples: outdated business models (e.g., print media), excessive debt, or industries in structural decline.

Avoid it by:

- Checking revenue trends (flat or declining = warning).

- Confirming positive free cash flow and manageable debt.

- Reading management commentary for credible turnaround plans.

Over-Diversification

- Owning too many stocks dilutes conviction and returns. Buffett’s concentrated portfolio holds fewer than 20 core positions.

- Focus on your best ideas, not 100 tickers.

Ignoring Qualitative Factors

- A low multiple doesn’t equal value if the company lacks quality.

- Great investors marry quantitative discipline with qualitative insight.

How to Apply Value Investing in Your Portfolio

Let’s translate theory into action. Here’s a simple five-step process:

Screen for Value Opportunities

Use online tools like Morningstar, Finviz, or Yahoo Finance to filter stocks by low P/E, low P/B, and consistent dividends.

Example screen:

- P/E < 15

- P/B < 1.2

- Dividend yield > 2%

- Positive free cash flow

Perform Fundamental Analysis

- Read the company’s 10-K or annual report. Look for revenue growth, stable margins, and debt control.

- Check management’s shareholder letters for strategy and transparency.

Estimate Intrinsic Value

- Use DCF or relative valuation to determine what the stock should be worth. Apply a margin of safety before buying.

Build a Balanced Portfolio

- Hold 10–15 diversified positions across sectors and regions.

- This reduces risk while keeping potential upside.

Review Periodically

- Every six months, reassess whether valuations still hold.

- Sell when price exceeds intrinsic value or fundamentals weaken.

Value Investing in Emerging Markets (Case: Vietnam)

Emerging markets, such as Vietnam, offer abundant opportunities for value investors because inefficiencies and lower analyst coverage create frequent mispricings.

For instance, according to Dragon Capital (2024), over 30 stocks on Vietnam’s VN-Index traded below 1.0 P/B despite double-digit earnings growth.

Sectors like industrial exports, banking, and consumer goods show strong fundamentals yet remain undervalued due to macro-volatility fears.

However, challenges include limited disclosure, liquidity risk, and governance transparency. Investors should:

- Focus on companies with consistent earnings and export exposure,

- Verify audited financials,

- Diversify regionally to reduce single-market risk.

The Psychology Behind Value Investing

What truly separates value investors from the crowd isn’t math — it’s mindset.

Markets are driven by fear and greed, and value investors profit from emotional extremes. When others panic, they see opportunity. When markets are euphoric, they stay cautious.

This contrarian temperament requires:

- Patience: ignoring daily price moves.

- Discipline: sticking to fundamentals despite market noise.

- Independence: thinking differently from consensus.

A 2023 CFA Institute survey found that behavioral biases (herding, overconfidence, loss aversion) reduce portfolio returns by up to 3% annually. Value investing, when practiced correctly, counters these biases through process and patience.

Value Investing Success Stories

- Warren Buffett (Berkshire Hathaway): Turned $10,000 in 1950 into over $100 billion today through disciplined value investing.

- Seth Klarman (Baupost Group): Known for holding cash patiently until clear bargains appear.

- Howard Marks (Oaktree Capital): Focuses on distressed assets with high margins of safety.

- Each of these investors shares common traits: independent thought, rigorous analysis, and emotional control.

Conclusion

Value investing is not just a financial strategy it’s a mindset built on patience, discipline, and rationality. While market trends come and go, the principles of buying undervalued assets, focusing on quality, and thinking long term have stood the test of nearly a century.